Legalese is tricky to parse on a good day. The term “reasonable” leaves plenty of room for creative interpretation, and “compliance” is tough to nail down when specifics are, well, vague. When you apply these terms to data security legislation, it gets even more tangled. How does a regional law change when it crosses internal borders? Who has jurisdiction? And how on earth is it all enforced when threats constantly evolve?

Despite the confusion, data regulation and legislation is incredibly important, even if it seems murky at first. Read on for an overview of some major cybersecurity laws and how they might affect you at both the business and consumer level. There are the ones we know the most about (HIPAA, COPPA, PCI), the one we keep hearing about (GDPR), and the new one in 2020 (CCPA).

How Are Cyberspace Regulations Split Up?

The world is segmented by borders, but the Internet is a communal resource accessible from almost anywhere. Still, legislation has to start somewhere. Most countries have some form of cybercrime and/or data protection legislation. The EU had a rough patchwork of various national laws dating from 1995. That was replaced by the GDPR in 2018, which broadly covers individual data rights across the whole region.

The United States has some federal laws organized by industry vertical, but so far nothing as far reaching and cohesive as the GDPR. To fill the gaps, many states passed individual laws. California is a particular leader in cyberspace legislation. It was the first to pass the Notice of Security Breach Act, in 2003. Naturally, other states realized that it’s a good idea to make companies inform users of data breaches and followed suit. California was again the first to pass legislation around the IoT, in 2020. Also launched in 2020 was the CCPA, which mirrors the GDPR in that it centers the residents of a specific region—in this case, California.

How to Ensure Data Compliance

Cybercrime and data protection legislation is constantly evolving. With so much legislation focused on the consumer’s place of residence, it’s impossible to know which laws apply to your business without going through them all. The parameters of “compliance” also differ from law to law. HIPAA is often case specific. The GDPR doesn’t accept your compliance unless you can prove it.

On top of that, laws based in a region halfway across the globe may suddenly apply to your company, depending on which demographics your website targets. Take the GDPR, for example. It’s currently the most cohesive data protection law in the world. Between the strict penalties and the near-definite possibility of someone in the EU visiting your website, most websites choose to comply no matter where they’re headquartered. Compliance includes informing consumers whenever you’re collecting data, even the default data collection that happens whenever you click a link. You might have noticed a recent tiny change to your web browsing habits; nearly every website you visit has a little popup informing you that they collect cookies. This isn’t new, but GDPR compliance made the announcement commonplace.

So how do you guarantee compliance? Long story short, it depends. It depends if the laws come from open discussion or behind closed doors. It depends on interpretation. It depends on your location. It depends on the data subject’s location. It depends on subjective definitions of a dozen terms and more.

It also depends on how much the company using your data wants to comply.

Hopefully, companies go above and beyond the call of compliance, which is one of the only ways to be completely sure they’ve met the criteria and prevent fines. The opposite approach, active noncompliance, often includes data dumping or blatant disregard because compliance is too expensive or time consuming—don’t be that guy.

Never assume you understand the full range of international compliance as it pertains to your business—even experts struggle to fully grasp the international interplay.

GDPR: General Data Protection Regulation

Where: The European Union

When: Since 2018 (published in all EU languages in May 2016, compliance wasn’t implemented until May 2018)

Who: Anyone who collects EU residents’ data

Most cyberspace legislation covers a specific state or nation. The GDPR covers the whole EU. It’s a big law, 88 pages total with 99 articles. And not everything is specific. Or, well, there are a lot of specifics. But their interpretation is where it gets confusing. The GDPR covers residents’ data, so it applies to companies anywhere in the world that have customers in the region or that even just process their data.

The GDPR replaced 1995’s Data Protection Directive (DPD) in two key ways. First, it brought vitally necessary post-Internet updates. Second, it’s a regulation rather than a directive, so it’s instantly applicable instead of needing further legislative action in each member state.

But because the EU’s governing body doesn’t have jurisdiction over every aspect of individual nations, the GDPR still isn’t completely uniform. This means there are variations across the region that might not be immediately apparent to companies checking their compliance status.

To fully comply with the GDPR, you have to design everything you do around data protection considerations. You also have to justify why you’re collecting consumer data (Article 25).

If you process data from EU citizens, you have to meet seven principles under the GDPR (Article 5). The legalese isn’t exactly obvious to the naked eye, so here’s the plain English translation:

- You will process data lawfully and transparently.

- You will only use the data for the stated purpose.

- You will only collect the data you need—no more.

- All collected personal data must stay up to date, and inaccurate data must be immediately erased and updated.

- Only keep the data as long as necessary for the stated purpose (or archived for defined and appropriate purposes) (Article 89).

- Protect the data (encrypt it).

- You are responsible for and able to prove compliance.

The laundry list of stipulations goes on to define your timeline for announcing a breach (72 hours), exactly what constitutes consent, and when data processing is allowed (Article 6). Maybe you need a Data Protection Officer, maybe not. And there’s an entire chapter (Articles 12–23) on how the GDPR defines an individual’s (the data subject’s) rights. With all that and more, there are still exceptions to the GDPR.

GDPR Exceptions

There are a couple of exceptions for government activities, but we’ll focus on ones that would pertain to companies. The GDPR doesn’t apply to these situations:

- The data subject is dead or a legal person (by definition this can include humans but usually refers to nonhuman legal entities, like corporations).

- The data isn’t processed for business or professional purposes.

GDPR Violations

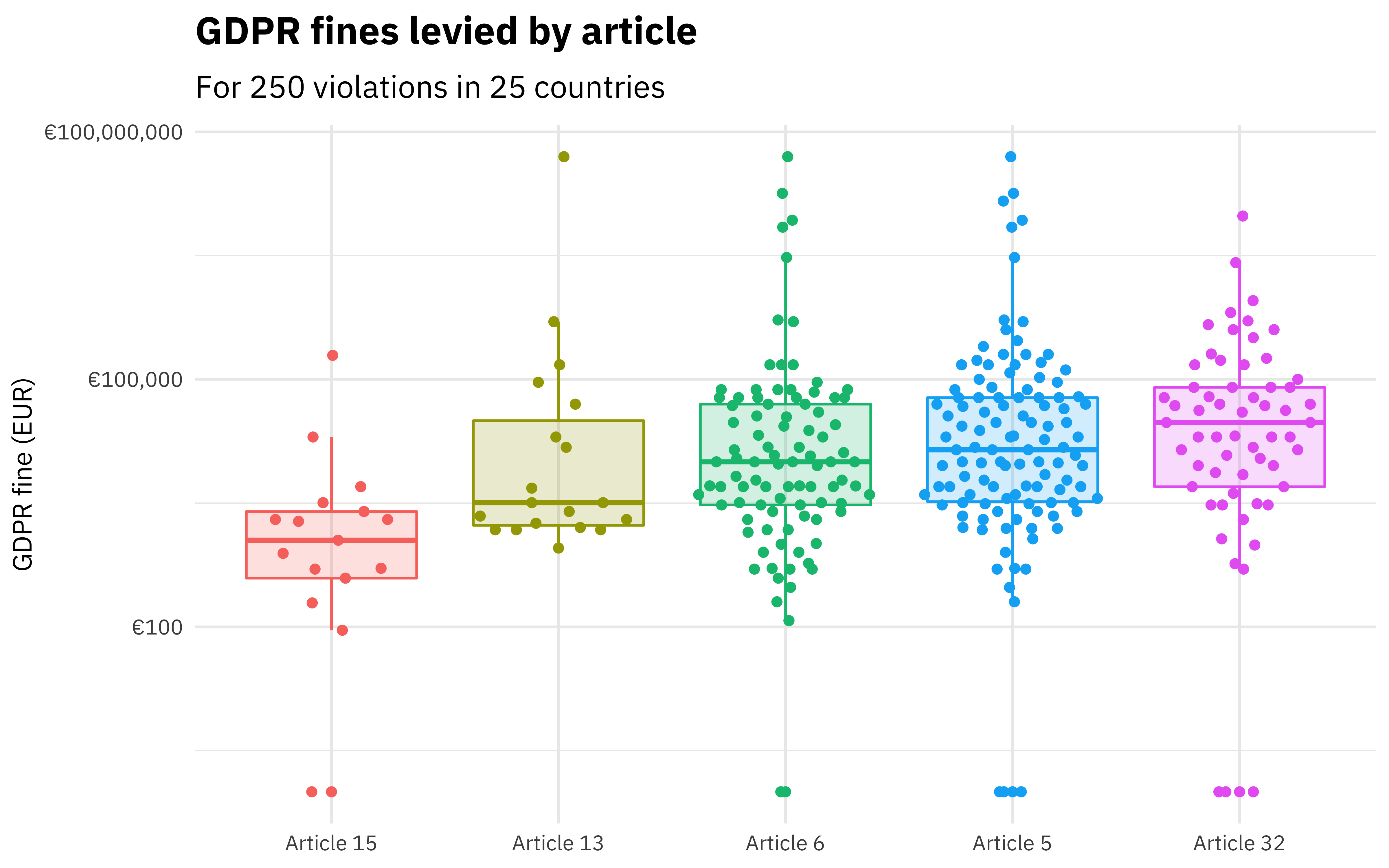

This is not an instance where you want to skimp on compliance. GDPR penalties are Steep with a capital S. The max fine caps out at 20 million euros or 4 percent of your global revenue, whichever is higher. For example, France levied a 50 million euro fine against Google for shady data collection practices around ad personalization. Google appealed the fine and was decisively denied.

Common violations include unauthorized data collection and failure to pseudonymize sensitive data, assess risk, or limit access. Here’s a fun data set showing which articles are commonly violated and the fines that accompany them:

HIPAA: The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act

Where: US Federal Law

When: Since 1996

Who: Healthcare professionals who handle Protected Health Information (PHI). This includes regular Personally Identifiable Information (PII)—like birth dates, SSN, names, and contact info—found in health records, as well as medical-specific information: medical record numbers, treatment and death dates, fingerprints, etc.

HIPAA regulates anyone who collects and processes PHI. Until 2013’s Omnibus Rule update, this applied only to covered entities—those actually in healthcare, like nurses and insurance companies. But your doctor isn’t the one actually processing your information, so the Omnibus Rule added “Business Associates” to the group: Non-healthcare folks who work in and around healthcare and have access to PHI. Think lawyers, IT, administrators, and your VoIP provider.

The Omnibus Rule is part of the Privacy Rule, which together with the Security Rule, make up the legs of HIPAA. Also under the Privacy Rule is the Safe Harbor Rule, which specifies which data has to be removed in order to declassify PHI.

Privacy Rule: Details how and when covered entities and business associates can and can’t use PHI data to which they have access.

Security Rule: Details the minimum security standards for managing electronic PHI. This separates ePHI into three sectors: Administrative, Physical, and Technical.

HIPAA Exceptions

Life loves to surprise us, and in emergency situations there are likely to be many instances that would normally violate HIPAA. In case of natural disasters like hurricanes or public health emergencies like COVID-19, people need to share PHI to help mitigate the situation. Maybe someone needs emergency medical care, or the CDC and local health departments need all the data they can get.

To accommodate these situations, the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) published a guide to HIPAA exceptions in emergency situations. Most exceptions occur on a case-by-case basis, but as with any emergency, it’s likely going to be an in-the-moment call. In any situation, HHS stipulates that individuals should share the minimum amount of PHI necessary.

HIPAA Violations

The HIPAA Enforcement Rule went into effect in 2006. It defines the procedures around handling violations, from how companies need to approach them to penalties involved. This includes the HIPAA Breach Notification: You have to inform people of any unauthorized PHI access within 60 days. Notably, this includes ransomware, when the data may just be encrypted and held for ransom rather than directly published. Depending on the severity of any single breach, companies have different timelines for informing HHS and OCR (Office for Civil Rights).

Fewer than 500 files compromised: Just include them in a yearly minor violations report to HHS.

More than 500 files compromised: Immediately inform HHS and OCR and issue a press release.

COPPA: Children’s Online Privacy Protection Rule

Where: US Federal Law

When: Since 2000

Who: Any website or app that targets children under 13

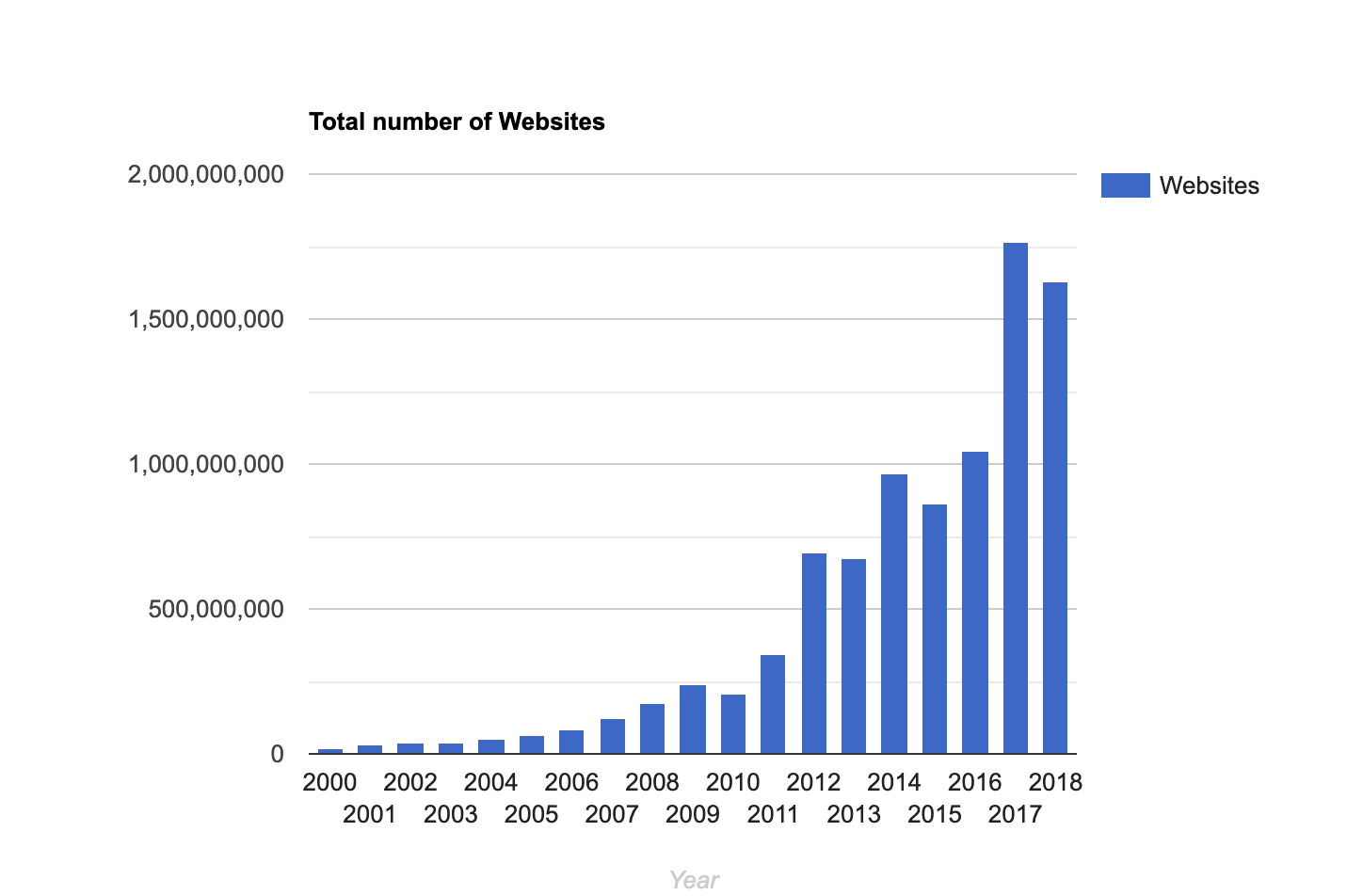

In 1998 the FTC surveyed 212 websites and found that 89 percent of them collected kids’ data. And of that group, 46 percent did not share what they did with that data (or that they collected it at all). Naturally, people weren’t fans. If you’re thinking, “Well, 212 websites isn’t that much; that could be a very select testing range,” you’re right, but also remember that this was 1998. The World Wide Web was only a few years old and basically still the Wild West.

Enter the first US privacy law written directly for the Internet: COPPA. Designed to regulate the collection of personal info on kids under 13, it mostly affects marketers. Think about targeted advertising today—would you want the same approach taken toward your 7-year-old playing games on your iPad or your 10-year-old nephew browsing the Internet for a school project? They don’t know to not share email addresses or other PII. COPPA doesn’t just affect web services that directly target kids, however. It also affects anything that theoretically could target kids, even if the key audience is general interest. You can collect data but only with verifiable parental consent.

These are fairly lofty goals but quite difficult to realistically implement—especially as Internet use has skyrocketed. Obtaining and maintaining clear parental consent isn’t easy when parents don’t understand the technology their kids use.

To Comply or not to Comply

In the beginning, whether or not to adopt COPPA compliance was actually a tricky situation for many. COPPA has a particularly wide reach, because while your website might not specifically target children, if it has content that appeals to kids through things like language or graphics, then the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) can determine you have to comply. The downside of noncompliance included huge fines and the negative publicity of not wanting to protect kids. On the other hand, compliance was vastly expensive, so many chose to do away with various features like email or chat rooms.

“According to Campanelli, some of the major costs of compliance include employing staff to compose and maintain the online privacy policy statements, hiring attorneys to review the policies, and coordinating the collection and secure storage of parental consent forms. Experts estimate that these costs would amount to between fifty cents and three dollars per child interaction, or up to $100,000 per year, for a medium-sized Web site.” —Inc.

The cost of compliance inherently limited kids’ access to the Internet. But FTC lawmakers argued that no child under 13 could fully understand the implications of sharing PII, hence the need for parental consent.

Until 2012, there were loopholes for third-party data collectors on websites. That update also added to the list of personal information protected under COPPA: IP addresses, usernames, device IDs, etc.

COPPA Exceptions

Most nonprofits are exempt from COPPA compliance, as are schools (but not third parties). There are also exceptions made for one-time contact, like entering a contest or asking a question, and multiple-time contact like signing up for a newsletter. These exceptions aren’t a blanket excuse for noncompliance but allow for specific data collection without requiring all of the paperwork.

COPPA Violations

Early COPPA fines went up to $11K per incident, but the FTC regularly increases the amounts. The first time a COPPA fine hit $1M was against social networking site Xanga in 2006, matched again two years later against Sony BMG Music. Major violations stayed in the tens and hundreds of thousands range until Oath (AOL) in late 2018 and Musical.ly (TikTok) in early 2019, at $5M and $5.7M respectively.

YouTube’s 2019 violation blew both of those out of the water. The aftermath of their $170M fine saw YouTube implement a new rule in 2020: Creators have to label their videos that are directed to kids. This means that the FTC can now hold individuals accountable for the content they upload to YouTube, which naturally stopped many creators in their tracks.

GLBA: Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act

Where: US Federal Law

When: Since 1999

Who: Financial institutions. This means more than just banks or your tax guy. Think anything to do with mortgages, appraisals, debt collectors, and some financial advisors.

GLBA, also known as the Financial Services Modernization Act, works to regulate how financial institutions handle peoples’ personal data. It came about primarily because of the 1998 merger that resulted in Citigroup, which was illegal under the 1956 Bank Holding Company Act (BHCA). The GLBA repealed parts of both the BHCA and the 1933 Glass-Steagall Act, both of which heavily limited any one financial institute from combining with one headquartered in another state, or another type (like commercial banks and investment firms), respectively. Any merger would result in an incredible amount of sensitive nonpublic personal information (NPI), and the GLBA attempts to protect that dragon’s hoard of desirable information.

The act is broken into three parts:

Financial Privacy Rule: Financial institutions have to share with each individual exactly how they intend to use their data. Consumers need to know if they can opt out of sharing their data with third parties. This notice goes out at the start of a relationship, each year afterward, and any time that changes are made so that individuals are always aware.

Safeguards Rule: Financial institutions have to actively protect said information they collect from customers. There are specific stipulations to this rule to ensure that all institutions have to take a solid look at their data protection practices, test them, and keep them up to date in order to comply.

Pretexting Provisions: Beyond making, testing, and updating data security plans, financial institutions also have to put effort into prohibiting pretexting, also known as social engineering. Social engineering is when someone tries to access private personal information under false pretenses, like impersonating an individual or phishing scams.

GLBA Exceptions

Most exceptions to the GLBA relate to the customer’s opt-out option. Because customers have to actively opt out of having NPI shared with third-party affiliates rather than opt in, this is highly exploitable, particularly for joint marketing reasons. Other exceptions to sharing NPI fall under situations like these:

- Fraud prevention and detection

- Legal compliance

- Anything related to a transaction approved by the customer

- Anyone acting in a fiduciary capacity

- Anyone with legal or beneficiary interest on the customer’s behalf

GLBA Violations

Violating the GLBA is no joking matter. For each violation, financial institutions can be fined up to $100,000 and individuals up to $10,000 and five years in prison. Early in the law’s history, the FTC hit several mortgage companies for violations, but the most memorable incident in recent history involved PayPal (Venmo).

Is This PCI Compliance?

It’s easy to lump PCI (Payment Card Industry) compliance in with GLBA since they both deal with financial information. However, PCI is entirely separate and in fact isn’t even a federal law in the United States.

“Surprisingly, US federal law does not mandate that businesses comply with the PCI standard (although a few states have laws that deal with PCI compliance). However, when you sign contracts with major credit cards that allow you to accept their cards at your business, you also agree to observe their rules—and that includes following PCI requirements.”

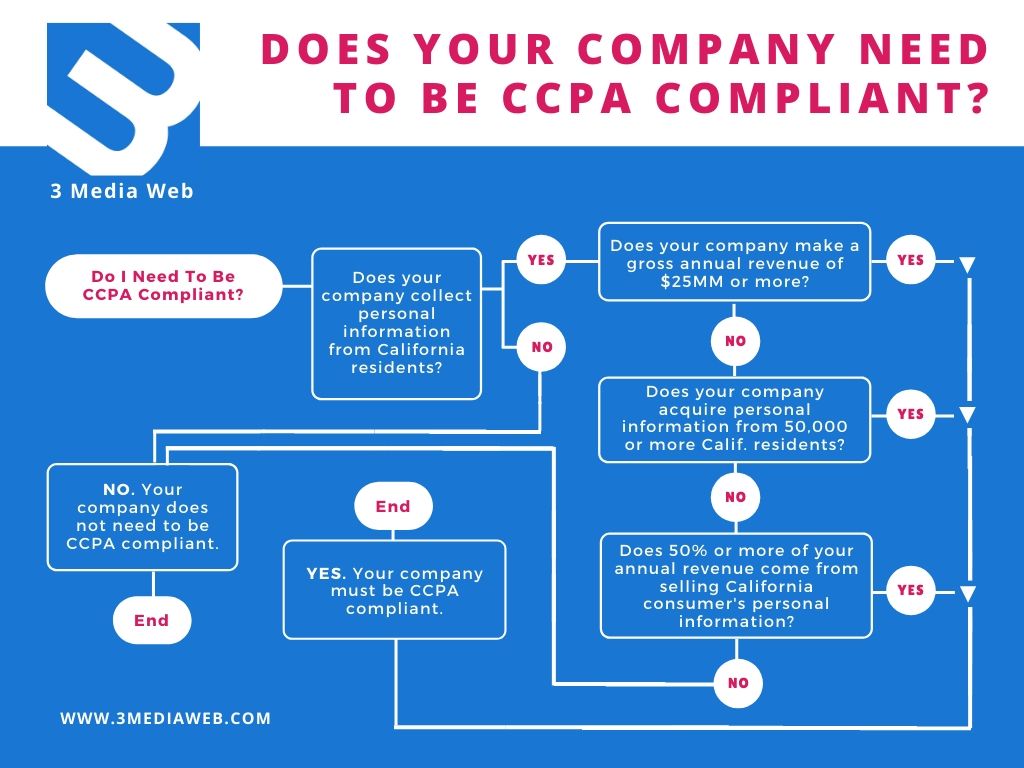

CCPA: California Consumer Privacy Act

Where: California

When: Since 2020

Who: Anyone who collects California residents’ data

The easiest way to wrap your head around the CCPA is to think of it like the GDPR but for Californians. Of course they’re not exact matches, but they do line up on a number of points.

There are a couple of new specifics that the CCPA introduced, namely probabilistic identifiers (see explanation below) and a right to delete without retaliation. Also, California consumers have much more access to the personal information that companies collect than consumers protected by any other law.

All of this means that companies are scrambling to figure out if they can find this information in the first place. It’s dangerous territory because consumers can sue companies for the first time. If consumers decide to opt out and not allow companies to sell their data, they’re protected from retaliation (i.e., getting charged more or having service degraded). Here are Californians’ five rights as described in the bill itself:

- The right of Californians to know what personal information is being collected about them

- The right of Californians to know whether their personal information is sold or disclosed and to whom

- The right of Californians to say no to the sale of personal information

- The right of Californians to access their personal information

- The right of Californians to equal service and price, even if they exercise their privacy rights

CCPA Exceptions

There are several exceptions to CCPA compliance. They also come with oodles of fine print. Like other laws, these categories aren’t blanket exemptions, but they provide the blueprints for figuring out if you may have some leeway. Exceptions to CCPA compliance include:

- Companies that don’t collect data from California residents, or the info is both collected and used out of state (i.e., prepare to look up each and every IP address origin)

- Employee info used entirely in employer–employee relationships (job applications, contractors, etc); employee info ≠ consumer info

- B2B relationships

- Warranty and recall information

- Data subject to other laws including:

- Financial: GLBA, California Financial Information Privacy Act (CalFIPA)

- Medical: HIPAA, Confidentiality of Medical Information Act (CMIA), and Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects (clinical trials)

- Consumer Reporting: Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA)

- Drivers: Driver Privacy Protection Act (DDPA)

CCPA Violations

Companies had a good bit of time to prepare for CCPA compliance. The law was approved in June 2018, went into effect January 1, 2020, and enforcement began July 1, 2020 (although the first case citing the CCPA showed up early). Fine amounts vary depending on whether the violations were intentional or not—up to $2,500 for nonwillful and up to $7,500 for willful noncompliance. While that might not seem like much to a larger entity, go ahead and multiply each of those amounts by the number of people affected and then decide if you should climb out of Scrooge McDuck’s money pool.

Besides the time allowed to prepare before the CA Attorney General started enforcing the law, companies have had years to document and track down the origins of data collected as they worked to comply with other laws like the GDPR. If you are hit with a CCPA violation, you have 30 days to comply before fines come into play.

Looking Ahead

The CCPA is the tip of California’s privacy iceberg. The California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA) is on the 2020 ballot. It would significantly up the ante for privacy rights and also see the California Privacy Protection Agency (CPPA) established.

While these are just a handful of data privacy laws effective in the United States, not everything is gloom and doom for data collectors. Consumers view companies that put effort into privacy compliance much more favorably. And that translates not just into heightened brand reputation but also financial gain in the long run. The United States is finally coming on board with data protection, albeit at the state level until a federal law comes into play. It’s best to not wait for that, as California, New York, and several other states have realized. Data privacy protection is here to stay, and it will only grow.