For most of us, the thought of life without Internet access this far into the 21st century verges on the absurd. We’re so tethered to the incorporeal cloud that one company recently offered a $2,400 reward for going 24 hours without screens. Computers, video games, everything in the “smart” category from watches to speakers to Alexa—the idea of cutting ourselves off from the Internet for a paltry 24 hours is as anxiety-inducing as the doom scrolling trend that led to this contest.

Again, that’s for most of us. As in, those who live in areas where 5G already rolled out and we have mixed feelings about screen time reports quantifying social media addictions. It’s easy to assume that lack of Internet access exists mainly in underdeveloped or highly censored countries. We could go on at length about geoblocking around the world, and particularly how countries tend to block Internet-based communications like VoIP. But first, let’s look at literal broadband access here in the United States, because it’s in worse shape than you might think.

Broadband Access in the US

The UN declared Internet access a human right back in 2016. The non-binding resolution came into sharp focus in the past year as pandemic shutdowns lit floodlights on areas with shoddy service, not to mention heavily censored regions. Unfortunately, a good chunk of the United States falls into the “shoddy service” category, or even worse, no access at all. This feels odd, doesn’t it, for a developed world power? Although after multiple COVID waves and a less-than-accessible vaccine rollout, it seems less like a surprise and more of something we chose not to notice if it didn’t affect us—a theme that could be the subtitle for the year 2020.

The state of broadband in the US is one of those tricky situations where we all know it’s incredibly unequal, but it’s hard to gather data specific enough to force change. As per usual with telecommunications issues, it comes down to infrastructure. Despite the UN resolution, the US has not approached Internet access as a necessary utility like water and power. Several other countries have gone that route, though. South Korea is particularly worth noting on that list, as their approach to Internet infrastructure no doubt played a leading role in that country’s 5G rollout during the 2018 PyeongChang Olympics. (Anyone else remember the Olympics? Boy, do we miss sports and general joyful gatherings over here.) Heck, Finland even made broadband access a legal right back in 2010.

Instead, the federal government let the largely self-regulated Internet Service Provider industry take the reins. It’s difficult to assess the extent of broadband dead zones when those in charge of providing access are barely regulated and therefore not held accountable for failing millions of Americans.

“The United States government has historically not seen fast Internet as something everyone should have, like it does water or even phone service, and the consequences are becoming frighteningly apparent. ‘I was responsible for this, and I failed,’ Tom Wheeler, who served as chairman of the FCC under President Barack Obama, told me recently.”

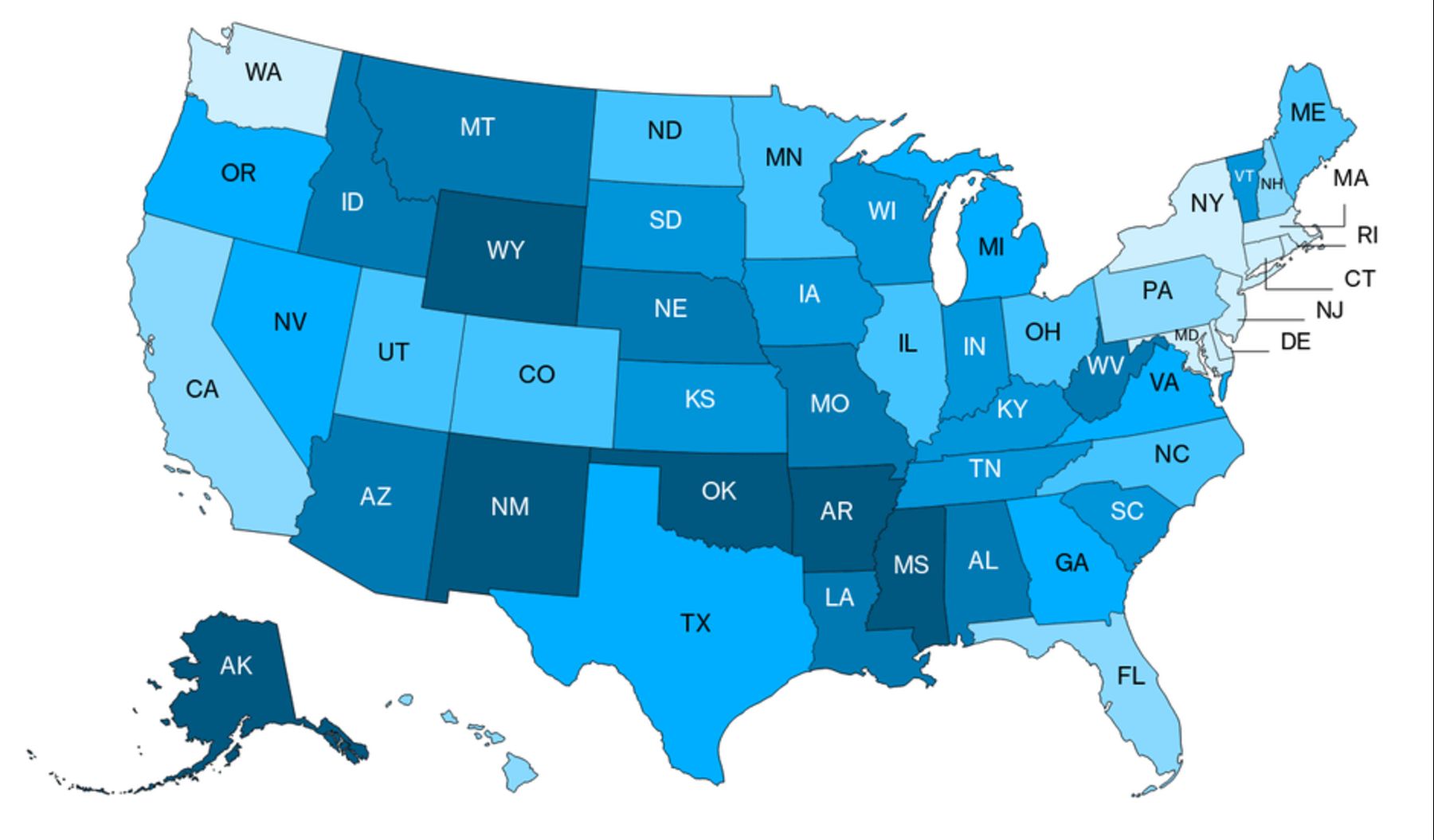

–The Atlantic

The FCC estimated in its February 2020 broadband report that 21 million Americans lack a fast Internet connection. That’s 6.5 percent of the population. Other estimates suggest the number is double that after conducting independent research. Why independent? Because the FCC report comes from ISP-generated data. Fun fact: If an ISP provides Internet service to just one household in an entire census block, then that entire block is listed as having access. So the broadband coverage maps that ISPs give to the FCC are wildly inaccurate. And it’s impossible to fix a coverage problem with doctored data. To end the digital divide, we first have to figure out who isn’t covered—both with literal access from built-out infrastructure and quality service that doesn’t break the bank.

Who Does the Digital Divide Affect Most?

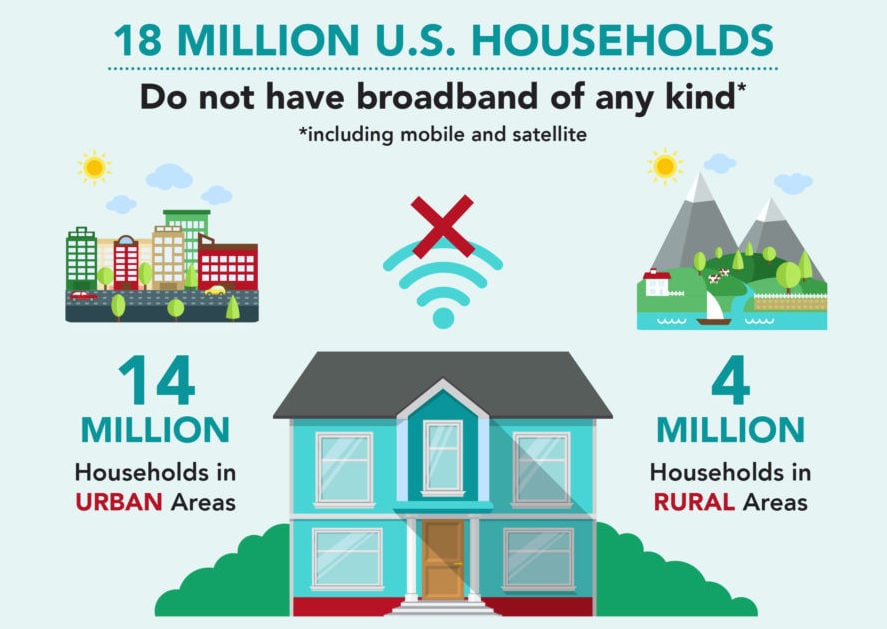

It should come as no surprise that a for-profit, mostly self-regulated sector has ignored “less profitable” areas—leading to the term “digital redlining,” which has exactly the same socioeconomic discrimination as its parent term, residential redlining. Going back to our assumptions on Internet access from the top of this blog, it’s also easy to assume that the digital divide mostly affects rural areas. For starters, it lines up with PSTN infrastructure issues. Plus it makes sense that an ISP would run a line past one house but not to its neighbor a few miles away. Even the FCC says the majority of those 21 million Americans without high-speed Internet are in rural America—but since we already know that number is grossly underestimated, take that claim with a grain of salt. In reality, deployment is only one factor in the digital divide. Adoption is another.

“Typically, Internet companies say there aren’t enough customers in certain areas for them to feel financially incentivized to go there. This occasionally leads to what advocates call ‘digital redlining,’ in which wealthy areas get online, while lower-income neighborhoods don’t. Similar to residential redlining, this has a disparate racial impact: Black Americans are less likely than white Americans to have a broadband connection at home.”

–The Atlantic

Progress is coming, but it’s slow moving. From 2013 to 2018, the FCC and the Department of Agriculture dropped $22 billion on rural broadband expansion. In 2019, the FCC at long last started to remedy the data collection problem. They voted to make ISPs provide geospatial coverage maps, rather than ones based on census blocks. This is all well and good, but it remains to be seen if ISPs and broadband lobbyists cooperate, let alone if the data is verified and validated.

Ending the Digital Divide

Until COVID-19 shoved all of us online from home, this issue tended to get buried under the plethora of inequalities vying for policy reform in our government. But once you brush off the misleading dust layer that are ISP coverage maps to see the reality, it’s impossible to separate the digital divide from the same systemic racism that led people to the streets in 2020. Most importantly, even before accurate data gathering, it’s necessary to acknowledge Internet Inequality as a result of structurally racist policies and deployment. The COVID homeschooling era may end soon, but there’s no vaccine for the digital divide, only action and accountability.