Opus is a relatively new audio codec that was created through a joint effort between several organizations based on two previously available codecs: SILK from Skype, and CELT from Xiph.org. Opus has seen a lot of press lately due to its receiving a newly IETF approved standard in RFC 6716. Beyond the new standard, Opus is interesting because of its technical claims, capability to provide high-quality real time audio encoding and decoding for a wide range of bit rates and sampling rates, and the fact that Opus is not only free, it's open sourced.

History and Development

Opus originally comes from two independent efforts: The SILK codec that Skype started developing in 2007, and the CELT codec from Xiph.org which was also under development in 2007. The first version of CELT became available in 2009, and shortly thereafter Skype joined the IETF and asked to create a working group to develop a standardized “Internet Wideband Audio Codec”. After significant debate and push back from many organizations who hold patents relating to current codec technologies, the IETF created a working group in February of 2010.

The working group resulted in collaboration between several organizations including Xiph.org, Broadcom, and Skype (Microsoft). By July of 2010, they had created the first working prototype of a SILK+CELT hybrid codec. In March 2011, the Opus implementation was beating AAC, and Vorbis in human listening tests.

Technical Information

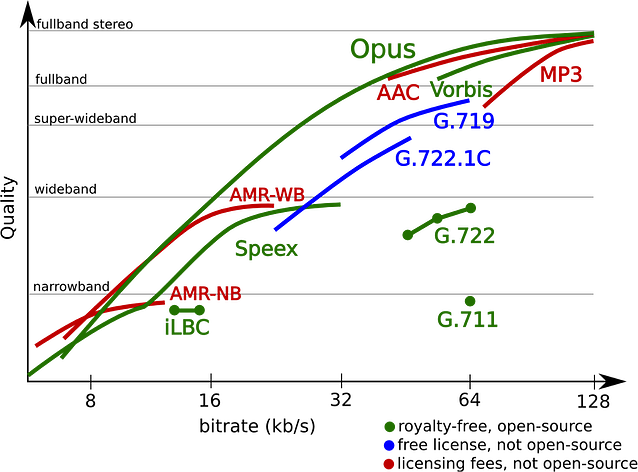

Opus is literally a hybrid codec that joins two separate codecs; it spans the range of narrow band to wide band sample rates 8-48khz. This is effectively the range of a PSTN phone call in G711 at 8khz to CD quality audio at 48khz. Opus also supports a wide range of bitrates from 6-510kbps and variable frame rates from 2.5-20ms.

What does all this mean exactly? Well, in short, Opus is extremely flexible, and because of that, it can be used for low bit rate voice over IP and outperform existing codecs such as speex and g729. It can also be used for high fidelity music transmission at quality that surpasses mp3. That said, Opus does not target usability at the extreme low end of bit rates. For example, Codec2 can use as little as 1200 bits per second (NOT kilobits) per channel.

One interesting thing about Opus is its hybrid nature. Opus uses a heavily modified version of SILK for encoding up to around 32kbps and only uses the CELT component once the bit rate exceeds 32kbps. Because of this, there is a noticeable shelf where quality increases, especially for non-speech as SILK is designed specifically for speech, when you pass the 32kbs bit rate and the CELT half of Opus “kicks in”.

Standards and Licensing

The final interesting piece of Opus is that it is, in fact, an IETF standard as defined in RFC 6716, and it’s also not only free to use, but it is open source and includes patent licenses to anyone who uses it. Why is this interesting? Well, it is all fine and good that the nice people at Xiph.org, and Skype created this codec, but also pretty meaningless until any one adopts it and includes support for it. In the hosted VoIP space, this means having SIP user agents: phones, and soft switch implementations that include the Opus codec.

Having the codec standardized is a big step towards spurring adoption. The RFC, itself, actually contains a reference implementation of the codec so that there is a working code base for people to adopt. This code is BSD licensed, making it freely available to use, and modify for personal or commercial purposes.

Due to this open nature, Opus 48khz already has implementations in Jitsi, and CsipSimple. I hope that with Broadcom, a major chipset manufacturer, being included in the working group that Opus will see its way into hardware soon, and we can all begin to enjoy high quality, open audio, and enhanced interoperability through codec standards. For today, you can use your favorite OnSIP-registered SIP client that supports the Opus codec and start making super high quality SIP to SIP calls using Opus.